This is a reflection of my father’s time at the Queensland Museum.

In late 1944, at just 16 years of age, Ivor Filmer walked down Gregory Terrace from Brisbane Grammar School one day, to the Queensland Museum. There, he asked the director if there was any chance of employment. Ivor was informed that most of the staff were at the war, and he would be ‘very useful’.

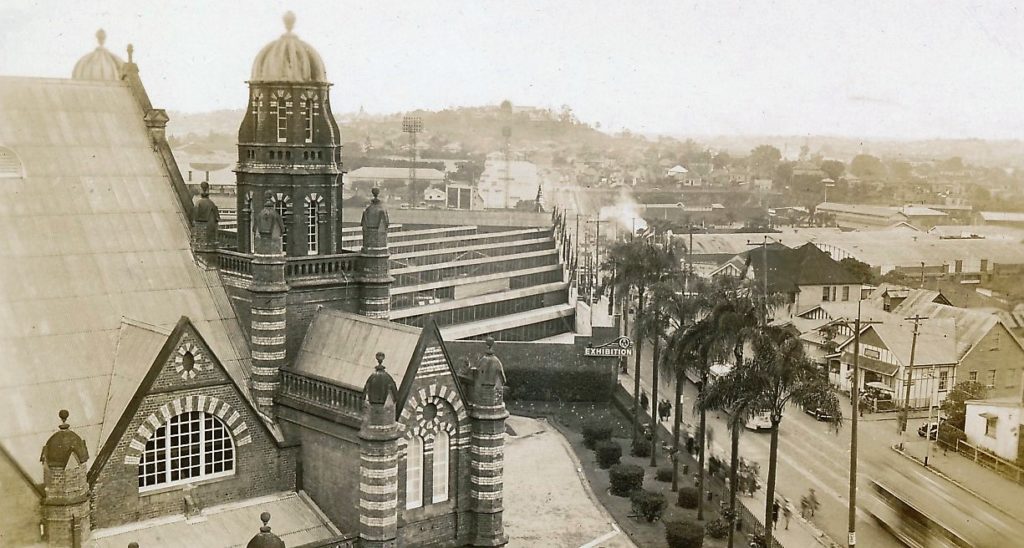

1946, taken during the RNA show

Not long after Ivor commenced the director, Heber Longman, became ill, and was on sick leave for long periods. So it was that Ivor became the junior assistant, at aged 16. At a time when a search on the internet for information was many decades away, Ivor was delegated to handle the enquiries on natural history from the public, and by post. He recalls that the information had to be found, and there was no one else to do it, so in effect he couldn’t help learning many things. His instruction was to elicit ‘two pertinent facts’ and the information would be given via phone to the director for confirmation, by Miss Murphy in the office. The large library, full of weighty tomes and priceless literary works, was Ivor’s domain. A ladder was available for access to high shelves.

Receiving a specimen (undated). Ivor on right.

As a young assistant in the museum at this time, Ivor did almost every job there was to be done. He cleaned and fumigated display cases and spirit tanks, ran messages, arranged displays, labelled specimens, filled up jars, made catalogues, registered acquisitions and identified specimens— sometimes with Mr Longman’s help, but often he had to do it on his own. When Longman was away, he answered most of the public enquiries. When Miss Murphy was away, he was clerk as well.

Ivor was enthusiastic about the museum and natural history. Daily, he kept a diary to record the tasks he completed and the conversations he had with Longman, who encouraged the young naturalist, discussing distribution, nomenclature, biology.

At Longman’s retirement there was excitement and consternation, when at short notice, on 11 June 1945, the Duke of Gloucester decided to visit the museum, and on that very day the director was away sick. The duke arrived, dressed in military uniform with the duchess by his side. They were accompanied by the governor of Queensland, Sir Leslie Wilson, and his aide. The welcoming party, comprising J. Edgar Young (honorary paleontologist), Michael Beinie (head attendant), and Ivor, guided the royal couple and the governor around the galleries. The duke then signed an historic bible, donated by J Wilkinson, the first member for Moreton in the federal parliament. According to Ivor, it was a dull overcast day, and matches had to be lit occasionally to show the duke a specimen or to light up a label. Looking back one wonders just what the duke thought about a state museum where matches had to be used for illumination of specimens and labels. The museum galleries were lit with electricity for the first time in their history only in August 1948.

On 14 August 1945, World War II ended. Ivor recorded the receipt of that news:

“A unique day in our history, and in my life. Peace was officially announced at 9.30 this morning, and at the museum we received the news with joy. The attendants rang the bell, shouting “Hooray!” through the galleries and Mr Longman and I found an old Balinese gong which we banged and made a loud ringing noise outside the back door, but there was no one there to hear us”.

Ivor particularly enjoyed the field trips. Many times he made expeditions with other staff, usually to collect perches for bird displays. They would catch the train from Brunswick Street to Mitchelton and then walk to Samford Road or to Ferny Grove, sawing off the logs they needed and carrying them back to the station in sacks.

1948, Ivor on right

Ivor also started assisting with taxidermy. “24 March 1947: an important day in my career— tackled my first skin”. He assisted in the maintenance of displays, and many other tasks, from 1944 to 1952. His keen interest in natural history persisted after he left the museum and he continued to send in road-killed and storm-washed specimens. While in charge of the Australian Inland Mission Hospital at Birdsville from 1957 to 1959, he collected more than 200 vertebrates, including rare mammal and bird specimens, some of which were mounted for display. He usually air-freighted the specimens from Birdsville to Brisbane and on one occasion he sent a live python, with two rats in the container to serve as food. However, when museum staff opened the box they found that instead of the python having eaten the rats, the latter had nibbled the python. In all, Ivor spent 8 years or so at the Queensland Museum.

Some of these notes are also located in the book A time for a museum: history of the Queensland Museum: 1862-1986. The authors utilised various notes from Ivor’s diaries that he kept at the time.

Recent Comments